Razer Gold Now Available in the Salad Storefront

Chefs, meet Razer Gold – the other ultimate digital wallet for gamers. Razer Gold offers a seamless means to purchase games and unlock rewards with …

The latest news on the Salad app, the latest rewards and everything that’s cooking in the kitchen.

We’re halfway through February, and we hope you Chefs had a great Valentine's Day. But instead of more chocolates and cards this upcoming weekend, how about a date with your

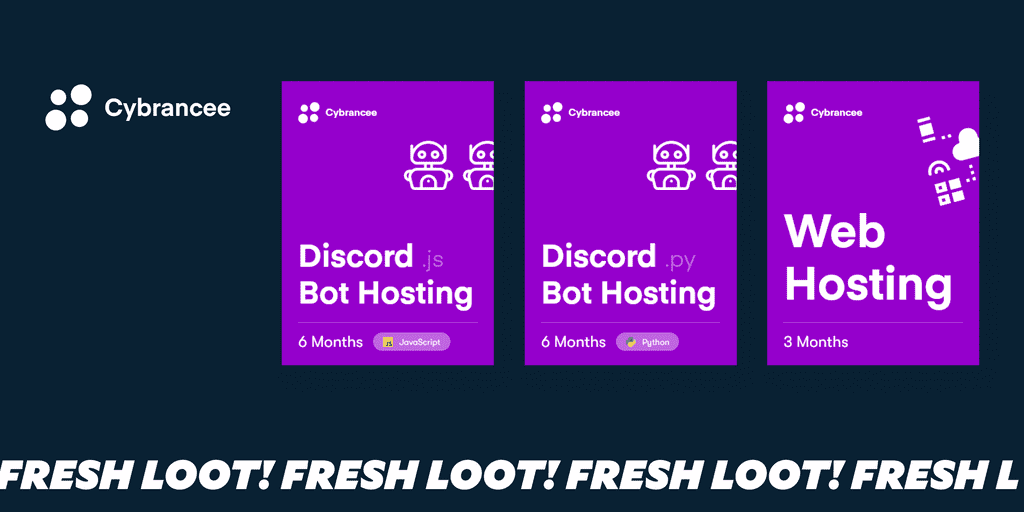

Online presence has never been more important, and managing web hosting for your various personal and professional projects can be both time-consuming and expensive. Whether you're crafting a custom Discord

Every Chef knows that Salad and Minecraft go together like croutons on salad. The power to earn with your PC, and the power to build the entire Earth out of blocks are

Chefs, meet Razer Gold – the other ultimate digital wallet for gamers. Razer Gold offers a seamless means to purchase games and unlock rewards with …

We’re halfway through February, and we hope you Chefs had a great Valentine’s Day. But instead of more chocolates and cards this upcoming weekend, how …

Online presence has never been more important, and managing web hosting for your various personal and professional projects can be both time-consuming and expensive. Whether …

Your posts, pictures, streams, videos, and creations dwell in various domiciles across the web: Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and more. While we’re more than the sum …

Gaming PCs are powerful tools, just look at what they can accomplish on Salad. However, even the hardiest tool needs sharpening, and Hone.gg is the perfect …

Salad is designed with gamers in mind. Our mission is to be the easiest way to monetize your idle PC resources. Put simply, we want …

Every Chef knows that Salad and Minecraft go together like croutons on salad. The power to earn with your PC, and the power to build the …

As every Salad Chef knows, our mighty machines are chock-full of valuable compute resources like processing, memory, and storage. Virtualization technology makes it possible to …

Containerization technology permits software developers to package programs, data, and dependencies—all the libraries and toolkits necessary to do the job—into a convenient and portable format …

Container workloads are the latest addition to Salad’s all-you-can-Chop buffet! Read on for the technical nitty-gritty, tips on getting started, and a few things to …

We’ve always said that Salad Chefs can do anything—and our upcoming Salad jobs will put the proof in the pudding! Starting today, eligible Chefs can …

Say hello to diversified fare. High-bandwidth jobs borrow idle internet connections to handle video data for folks streaming on personal privacy software. It’s like running a …